Editor’s note: This is installments two and three of a brief history of the Puerto Rican people’s fight for freedom. You can read installment one here.

Photo/Library of Congress.

Installment 2

Forging of the Puerto Rican People: Class Struggle

From 1791 to 1804, French St. Domingue, the most profitable colony in the world, with slave labor producing 40% of the sugar and 60% of the coffee exported to Europe, had a slave rebellion turned national liberation struggle. Rival imperialist powers looked to fill the void in the sugar and slave market, at the time two commodities as interlocked as capitalism and colonialism. After three hundred years of neglect by Spain, the small colony of Puerto Rico that had served it as a military garrison and strategically located waystation—a gateway to the Caribbean and the hemisphere—became in Spanish merchants and financiers’ eyes a place where there was a profit to be made.

Meanwhile, a weakened Spain, within a decade to face Napoleon’s occupation and in two the loss of almost all its colonies in the Americas, acceded to Puerto Rican trade with England and the U.S., opening up in the 1820’s. During that pivotal period of wars of independence of Spain’s colonies in the Americas and the Haitian slave uprising, Puerto Rico became a destination point for the French and South American criollo planters displaced from the liberated colonies. They came with their slaves, tools, machinery, and capital, induced by the Spanish regime’s offer of land and unimpeded access, and they set up shop in the Island. It was a market enterprise involving acquisition, sale, and exploitation of slaves, land, and equipment, mainly exporting the cash crops of sugar and coffee. Europeans with means—English, Irish, Germans, French, Mallorquins, Basques—would also take advantage of the opportunity. Over time, the wave of new planters and merchants would become creolized, Puerto Rican. The rising landowning class—creole and newly arriving—were incentivized to produce for the growing North American and European market. But they were constrained. They needed land and labor.

One source of labor was slavery, but the English abolition of the slave trade in 1807 made it increasingly expensive and difficult to get this labor, even with the slave market provided by Dutch and French colonies. Since the beginnings of the plantation system in the last quarter of the eighteenth century and throughout the period of slavery, free people of color (mixed-race and black) outnumbered slaves in the labor market of Puerto Rico. Nevertheless, as sugar and coffee production grew so did the slave population: 6,537 in 1776, 13,333 in 1802, 18,621 in 1815, 34,240 in 1830, and peaking at 51,265 in 1846 (according to the “official” census).

At its peak, slave labor represented 11% of the total labor force, but it was strategically placed in the critical sugar and coffee cash crops. The enslaved people responded to their exploitation and oppression with sabotage, escape, and rebellion, while the hacendados (big landowners) and Spanish imperialists increased their repression. In 1812, the Spanish governor orders that a slave disrespectful to the master get 50 lashes from authorities and then face the “owner’s” lashes. If the offense was violent, punishment was doubled. With greater vigilance, there were less large-scale escapes but many more individual runaways. Those not chancing it after 1850 got organized and demanded better clothing, shorter working hours, better labor conditions and food, an end to sexual exploitation, and increased negotiation between slave and master. Slaves gained increasing rights to work for themselves on their own time, making money to buy back their freedom.

The criollo and new planters needed land and greater access to labor, much like the early English capitalists, who turned to the Enclosure Acts to appropriate common land and force the peasantry into urban factories. In the Island, the hacendados needed to strip the land from the jíbaros, who had subsisted on it for centuries, and put them to work, alongside slaves, to produce sugar on the coastal plains and coffee in the interior highlands.

Since the last quarter of the 1700s, the criollo planters had been working on the continual expansion of an export economy at the expense of the jíbaro’s cultivation of subsistence crops.They got passage of the work pass law of 1849 (Reglamento de Jornaleros), obliging country folk with little or no land to carry a work pass, or libreta, recording their pay, time worked, debt (for advanced salary), and the landowners’ comments on their work and character. The jíbaro had to produce a (non-existent) title to the land to avoid forced labor on the hacendado’s land—becoming a jornalero, or day laborer. A poor rating in his libreta shut off work elsewhere, so the libreta became a tool to tie the laborer to a particular hacendado. This forced labor of the jornalero became known as white slavery (although jíbaros were not just white).

The jornaleros weren’t paid in money, but in vouchers good only in the planter’s, or hacendado’s, store, the only place the laborers could get what they could not provide for themselves. The criollo bourgeoisie and European financiers and merchants buying the Island’s agrarian goods (and dealing in slaves, machinery, technology, and know-how), all profited. Ultimately, of course, the criollo planters were restrained by Spanish interests and politics and at the mercy of the international marketplace. These hacendados went through good times, bad times, and catastrophe over the course of the 19th century, following the rise, downturn, and fall of Puerto Rican sugar. Their death knell was tolled in 1898 when American capital took over the sugar industry in Puerto Rico.The good times for the criollo hacendados had lasted to about 1870, when Cuban competition in sugar, abolition (1873-6), the fall in sugar prices, and lack of capital and new technology began to make their impact.

Installment 3

Rebellion Against Empire

Throughout this history of the Island, those who labored—black, brown, and white—also resisted. Peasant forced labor was not easy to get and, when gotten, not productive. The slaves, on whose labor sugar production depended, ran away, sabotaged, or rebelled. More than 40 conspiraciesto take over towns or the whole island or to assassinate white overseers have been documented, with many more acts of rebellion leaving no official paper trail.

One localized uprising, in the central-western hinterland of the island, became forever proudly ingrained in the national consciousness of the Puerto Rican people. In the coffee highlands of Lares, criollo planters and businessmen joined by small merchants, slaves, jornaleros, free black and other laborers rose up against the town-based Spanish merchants who had been keeping an iron grip on trade and credit. It was a classic anti-colonial alliance of growing national forces under the lead of the local bourgeoisie revolting against the imperialist master.

The jornaleros burned their libretas and, alongside the slaves, set fire to the fields. In this insurrection of the Grito de Lares (Cry of Lares), the colony turned against the imperialist. “The leaders of the insurrection were all coffee farmers. The working men who seized Lares were coffee pickers. And those arrested by the revolutionaries were the major (Spanish) coffee merchants and creditors of the town.” It was an uprising against the libreta, slavery, and Spanish domination.

At midnight on September 23rd, 1868, perhaps as many as one thousand men, poorly armed and without training,seized Lares and the local Spaniards, the town’s businessmen. They then moved on to nearby San Sebastian, where the Spanish military (forewarned by a town snitch) overwhelmed them. It was Spanish firearms against the criollos’ machetes and clubs. But no one remembers the defeat. What is commemorated every year to this day and continues to inspire the struggle is the people’s affirmation of self-determination and their will to struggle.

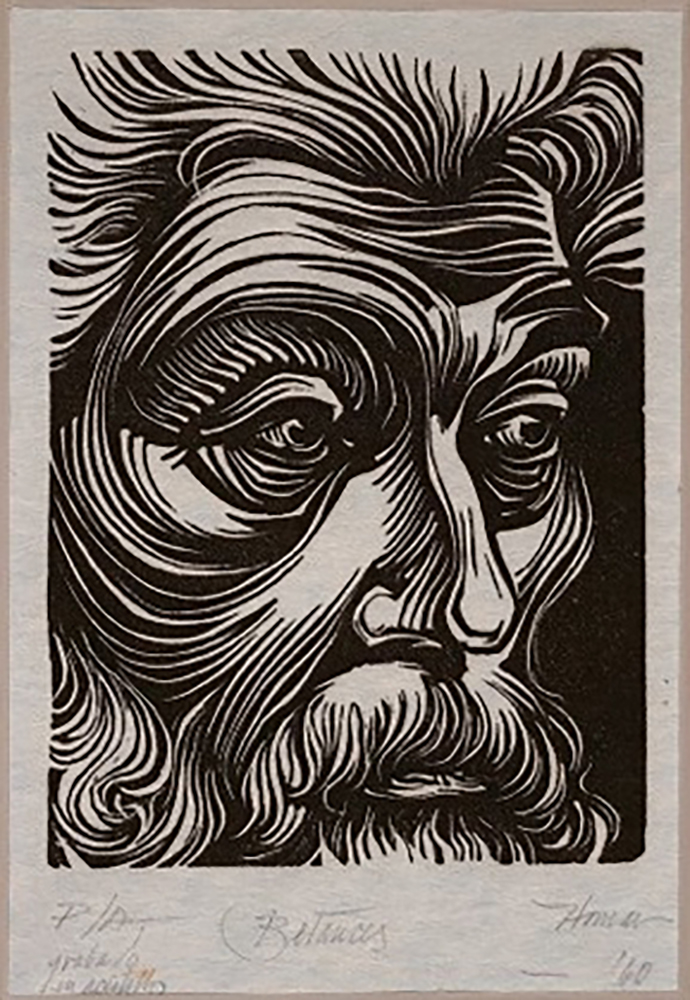

Behind Lares, there were also others operating from exile, raising money and arms, forging alliances with revolutionaries throughout the Americas and Europe, engaging in the diplomatic front, supporting the republican cause in monarchical Spain and independence for Puerto Rico and Cuba. Two such figures during the second half of the nineteenth century were Ramón Emeterio Betances and Eugenio María de Hostos, abolitionists, separatists, and internationalists, and diplomats for revolutionary Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and their homeland. They’d been preceded earlier in the century by Antonio Valero de Bernabé, who as a teenager had fought against Napoleon in Spain and then, when the king was restored to rule, fought the Spanish in the independence wars of Mexico, Peru, Venezuela, Colombia, and Panama. He wanted to carry the war against Spain to Puerto Rico and Cuba, but conditions were premature.

In 1848, a 20-year-old Betances studying medicine in Paris took up arms in the workers’ uprising. He defended independence for the Antilles and abolition, clashing with his father, a mixed-race merchant and slave-owning hacendado. Betances affirmed they were “prietuzcos” (“of darker shade”), not “blancuzcos” (“whitish”). Back in Puerto Rico in 1856, Dr. Betances organized the abolitionist society, spearheaded the independence movement, and led the effort against a devastating outbreak of cholera, treating slaves and poor people against the Spaniards’ demands of preferential treatment. Six times he was expelled for his revolutionary activity, from Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and St. Thomas. Returning to France, he collaborated with Dominican, Cuban, and European revolutionaries in the Caribbean, represented Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Haiti in Europe, and raised funds, arms, and recruits for the Cuban War of Independence. In Puerto Rico, Betances is remembered as the “Father of the Homeland.”

Eugenio María de Hostos was an educator, philosopher, writer, abolitionist, and social scientist. While studying law in monarchical Spain, he participated in the republican (anti-monarchical) movement, opposed slavery, and favored autonomy (local self-rule with ties to Spain) for Puerto Rico and Cuba. Unsuccessful, he left for New York, where he joined the Cuban Revolutionary Party, worked for Cuban and Puerto Rican independence, and advocated for an Antillean Confederation of Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and Cuba. As an educator, he championed empowering women and workers and a transformative educational philosophy and pedagogy. He helped establish the first teachers’ school in the Dominican Republic and the public education system of Chile. In Peru, he defended women’s right to enter the university and denounced the exploitation of Chinese labor. Hostos was also a brilliant thinker, essayist, and novelist. A lifetime dedicated to justice and the dignity of the people of Latin America earned him the epithet of “Great Citizen of the Americas.”

Betances and Hostos came from elite positions as sons of well-to-do families and sided with the laboring masses, but at the heart of the motion towards freedom in Puerto Rico was the action of the people themselves, early on, the Taíno, African, and runaway Spanish soldiers and sailors and by the 19th century, in what’s been called the counter-plantation culture rooted in African and Afro-Puerto Rican resistance, their heirs, now forged into a people, fighting colonial controls. The resistance was direct, as in escape and rebellion, and camouflaged, for example in the Haitian-derived bomba rhythms hidden in the melodies of jíbaro music that the elites tried to pass off as “white.” In setting up the jíbaro as the representative of the nation’s soul, they tried to strip him/her of Black and indigenous roots. But these roots asserted themselves, directly or camouflaged. It was the old cimarronaje, the culture of the runaway, imposing itself by any means necessary.

Another motion in place towards the second half of the nineteenth century was the forging and emergence of a working class gaining consciousness of itself, stirring and then asserting its power. Its seeds are in the urban guilds arising around midcentury of shoemakers, tailors, seamstresses, blacksmiths, laundresses, master carpenters, embroiderers, coopers (barrel makers), confectioners, hatmakers, bakers, and so on. Among these are the cigar makers, or tabaqueros, whose numbers grew with the industry and the appetite, especially, of the U.S. market. Brought together in shops, as in Cuba and elsewhere, and literate (mostly self-taught), they engage in discussion, hiring a lector to read from newspapers, romantic or naturalist novels, and anarchist and socialist tracts to stimulate the dialogue and debate. They will be at the forefront of a powerful working-class movement emerging by century’s end.