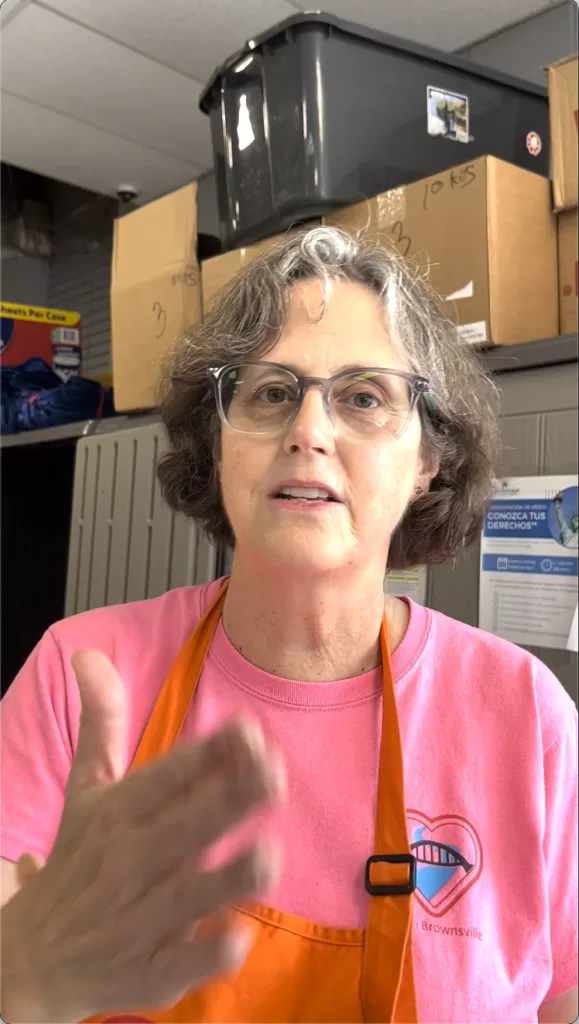

Editor’s note: Andrea Rudnik is one of the co-founders of Team Brownsville, an organization of volunteers that assists hundreds of migrants and refugees each day in Brownsville, Texas. Bob Lee of the People’s Tribune interviewed Andrea at Team Brownsville’s assistance center, across the street from the bus station in Brownsville, on Dec. 3, 2022. You can find an additional video interview with Andrea on the People’s Tribune YouTube channel at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_hnMUn2QrK4&t=1s. Both interviews were done in conjunction with Witness at the Border’s recent Journey for Justice along the border. To learn more about Team Brownsville and to donate, go to teambrownsville.org.

People’s Tribune: How long ago did you help found Team Brownsville?

Andrea Rudnik: We started in July of 2018, at the peak of family separation and metering [of migrants at the border]. And we had a slow backup of people on our international bridges here, people that were waiting to apply for asylum and suddenly were stopped because of metering. This was pre-MPP [the Migrant Protection Protocol, or “remain in Mexico” policy for those seeking asylum], but metering also stopped them. And then our eyes were really opened to people being left off from the detention centers at the Brownsville bus station with nowhere to go. They were mostly men, sleeping on the streets of Brownsville, that at that time, nobody was really paying too much attention to. So we started coming to the bus station with backpacks and hygiene kits and clothing and things like that. And we’ve gone like this in an uneven pathway because with every change of law, with every change of city arrangements and things like that, we’ve had to change what we do. So we work here and we work in Matamoros (Mexico), in the MPP encampment. Now, we’re supporting NGOs that are in Reynosa (Mexico) and in Matamoros, and we don’t spend as much time there. We do go across, but not daily like we did during MPP, so most of our hands on work is right here in the welcoming center.

PT: And do you live here in Brownsville?

AR: I do. I’ve lived here 36 years. I was a special education teacher in the Brownsville Independent School District. I’ve taught here for 30 years, and I’m a mom and a grandma. I actually grew up in upstate New York, but we made our way here. I’m retired [from teaching] now.

PT: What prompted you to do this work?

AR: Well, when you work in the Brownsville Independent School District, you are serving kids that are in need – a lot of kids that are undocumented, a lot of kids that come from family situations where they struggled greatly to get to Brownsville. And so when I found out about the need here, right here on our border, in our backyard, I was called to do the work. I just right away started collecting donations, taking them across, feeding people in Matamoros, coming to the bus station. So it’s over the last four and a half years, it’s really taken over my life.

PT: How did you go about soliciting donations and getting other volunteers?

AR: Well, initially we just got on social media and said, we’re doing this. We’re feeding people on the bridges. We’re feeding people in the bus station – can you help? And because we work in the school district, and it’s a big school district, we know people. And so people started to just donate; they’d say, hey, I’ll bring you a case of water. I’ll bring you snacks. And that’s the way we started. We started just posting things. And then, Facebook lets you do what they call personal fundraisers, because we were a grassroots organization. We were not a 501(C)(3) at that time. And people just started donating. I started writing stories about what we were doing, what we were seeing, and people started donating. And then a year later, we actually became a 501(C)(3) organization.

PT: How did you get this building?

AR: This building is owned by the City of Brownsville. It was a jewelry store and that jewelry store closed 20 or 25 years ago. It just sat here vacant. There are many, many vacant buildings in downtown Brownsville. And so Brownsville is going through a kind of revitalization right now, or renovation. So they basically said to us, we’ll rent you this for free, just clean it up. And it needed a lot of cleaning, serious cleaning after 25 vacant years. So we had to do everything from the ground to the ceiling, to the electricity, to the bathrooms, everything. So this belongs to them and we’re here as long as we’re needed or they want us here, basically.

PT: And so the migrants coming here are people who have crossed the border, have been picked up, gone through detention, and been released?

AR: Yes. So this is how they come [referring to the bus pulling up outside]. This is a bus that’s coming from Ursula, which is the Customs and Border Patrol facility in McAllen. And so usually the people come from Ursula in buses like this, and about 50 people come, sometimes all men, sometimes a mixture of men and women. We get way more men than women. Women and children don’t come on these buses. They usually come in the vans. And the women and children we’re seeing right now are coming as Title 42 exceptions. [Title 42 is a health law that has been used to prevent migrants from entering the US.] So they’re actually crossing the bridge, going through a different process, and then they’ll arrive here actually from the immigration building over on the bridge. And so this is a different population here that you’re seeing getting off the bus right now. And you can see that the Border Patrol agent showed up and is standing there. They do that always, just kind of have a presence there, stand there looking at them, making sure that they know that they’re being watched.

So from here, they’re processed, they go in [to the city building across the street], the city enters their name into a computer, all their information, and then whoever their sponsor or their family member is, is sent an email that says, your family is here, here’s what you need to do. And so they’re sent links for the airports here, the bus station, the different lines. And they’re told, okay, your responsibility now is to get tickets, if your loved one can’t leave until tomorrow, here are the hotels, you’re responsible for getting them food, getting them a taxi to the hotel. I mean, they [the migrants] are basically told this is your responsibility, and go.

PT: Whether they have any money or not?

AR: Correct. And, there is definitely a population of people that come that really don’t have money, that don’t have the means. And so the city kind of works with them all day long, has them call anyone they know and tell them, I’m here, can you pay for my ticket? And if in the end that doesn’t work, we do have a shelter here, the Ozanam shelter, that is primarily used as a homeless shelter, but also takes in migrants as well. And so they can go to the Ozanam Center, but they can only stay there for three days. And so sometimes we’ve had people that have spent their three days and do not have money and do not have any way of going to where it is they need to go. And sometimes they come and they don’t even have sponsors, so it becomes a bigger problem, like, okay, you don’t have any money and you also don’t have anywhere to go, so what’s going to happen? And so then we start looking for resources, shelters in this immediate area and also just in Texas as a whole. We know there’s a few shelters, one that we use in Austin, one in Houston. There’s one in San Benito that takes them. So it just depends. It varies from person to person.

We try to find them a place and we try to find them someone, a sponsor that can maybe pay for a ticket. That’s infrequent and it’s not something that we announce because it causes great problems. So we’re always walking that fine line between wanting to serve, wanting to give, and also having to respect the city’s control on the situation. They don’t want us to let people know about the shelter early in the day. They want to tell them at the end of the day. They don’t want us to tell people that, yes, there might be somebody that can assist you buying a ticket. They want to tell them that at the end of the day when they’ve kind of exhausted all their avenues of trying to get them to buy a ticket. And people come with different expectations, too. Sometimes people come with that expectation that everything will be paid for once they get to the United States, so that causes some problems.

PT: And so this [building across the street], this is where the city processes people?

AR: Yes. And we are not allowed in there at all. They will not allow us to enter. So we say there’s a great lack of transparency, and we hear different stories. Some people are fine and they get their tickets and they go on their way and great. And then you hear other stories from people that feel like they were not treated well, or things didn’t go well for them in there. And it’s hard to respond because we don’t have any access to the place. We’re clearly disinvited, you know? So it’s not like they want to tell us anything.

PT: Do you feel like you get enough supplies? Do you have a regular flow of supplies?

AR: We never have enough supplies. Never. We get a donation and it goes. You saw what happened here. So for example, I just ordered belts. Belts are one of the more expensive items because it’s hard to find a belt that’s cheaper than about $3 or $4 a belt. Some people have gone to like, the Salvation Army or Goodwill or things like that and have brought belts. We just never have enough belts. So there were, I don’t know, 18 or 20 belts, and a man walked in and his pants were falling down. I mean, they were all the way down to here. And so I said to Kathy or Martha, he needs a belt. And so he went looking for belts, came out with a belt, and immediately 20 other people needed a belt. That’s how it goes. Right. They saw him getting a belt and it was like, hey, I need a belt. And so there they went and, okay.

We try to give the kids each a book. We don’t have any books in Creole. I wish that we did because we’re getting more Haitian children now. But we do have books in Spanish and so we try to try to give every child at least one book. And so the parents kind of light up with that idea.

Bob Lee is a professional journalist, writer and editor, and is co-editor of the People’s Tribune, serving as Managing Editor. He first started writing for and distributing the People’s Tribune in 1980, and joined the editorial board in 1987.