Editor’s Note: Below we reprint a slightly edited version of a talk given by Chris Mahin on April 30 at Harold Washington College in downtown Chicago. Chris Mahin is a book seller and people’s historian. He is also an editorial board member of the People’s Tribune.

It’s an honor to be here! It’s appropriate that we have a discussion like this at Harold Washington College because Harold Washington himself was one of the people who fought to get May Day remembered in this city when he was mayor. He was mayor on the occasion of the centennial of the events at Haymarket Square — in 1986. He made sure that there were commemorations that year. They were the first official commemorations in Chicago in a long time.

I’d like to talk about what happened to create the internationally known holiday of May Day, a holiday that began just a few blocks from here, but yet for years, was totally blacklisted in this country, ignored deliberately, and not celebrated. But I really want to hear your thoughts about what the meaning of May Day is for students today.

May Day begins in 1886, which is exactly 21 years after the American Civil War. The American Civil War is over, and as a result of that, there’s an explosion of industry and an explosion of the division between rich and poor in the country.

Chicago in 1886 is the fastest growing city in the entire world. Immigrants are flooding into the city from all over the world, particularly from Europe. You have this intense division between rich and poor in the city. You also have a situation where nothing is done to alleviate poverty. There’s no Social Security, no unemployment compensation, no workers’ compensation, there’s nothing. So if you’re poor, if you’re out of work, you are out of luck. As a result of that, all over the United States, there’s an intense strike wave that begins in 1886 in a fight for the eight-hour day. On Michigan Avenue, there’s a huge demonstration on May 1st [1886] led by some very militant labor leaders.

A few days later, there’s a strike south of here at the McCormick Reaper Plant. Several workers are killed at the strike. So the leaders of the labor movement at that time called for a rally to protest that police killing. It’s held at a place called Haymarket Square, which is right over at Randolph and Des Plaines streets, just a few blocks west of here. And I would urge you at some point to go there and to see the monument that we finally forced the city to erect, after years and years of campaigning for a monument to what happened at Haymarket Square.

So, there’s this rally that’s called on the night of May 4th. It’s very hastily organized on one day’s notice. It starts late. The sky is threatening rain. The speakers go on too long. By late in the evening, the rally that organizers had hoped to get 20,000 people at, but only got 2,000 people at initially, had dwindled to 200 people. The speakers are droning on. One of the speakers makes a tactical mistake, speaking symbolically, and says: “You must strangle the law.” That’s used as an excuse for 176 cops to march down the street, marching north, and with Winchester rifles, order the rally to disperse. The person on the stage — an English immigrant, one of the leaders named Samuel Fielden says, “But officer, we are peaceable.”

At that point, from inside the crowd, someone throws a bomb. It arches through the air; it lands in front of the police officers. It explodes; it kills one police officer immediately. All hell breaks loose. The police start shooting wildly. They kill all sorts of people. People are dragged to the police station where they’re bleeding on the floors of the police station. And then there is a wave of hysteria against union organizers, against particularly immigrant workers, against workers who speak German. The police break into trade union halls. They break into German athletic societies. If you recall the hysteria after 9/11 or what happened to Japanese-Americans after Pearl Harbor, that’s the atmosphere: Anybody is suspect. The police hunt down some of the key leaders of the union movement and the revolutionary labor movement in Chicago and arrest them.

Eight people are accused and are about to stand trial. Seven of them were born or raised in Germany and are immigrant workers. One is a guy by the name of Albert Parsons, who was from Texas. He managed to escape at first. There’s this gigantic campaign of hysteria by right-wing media, anti-union media. (The Chicago Tribune at that time was kind of like Fox TV today). Before the trial opened, Albert Parsons had managed to get away and is safely in Wisconsin. He makes the decision that he can’t in good conscience let these seven immigrant workers stand alone. Albert Parsons comes back to Chicago on the first day of the trial. During the jury selection, he walks into the courtroom and says, “Your Honor, I have come back to stand trial with my innocent comrades.”

They go to trial. The trial is a travesty. The jurors are all selected mainly from Marshall Field’s department store even though Marshall Field was one of the guys who wanted the defendants to hang. So you have a biased jury, you have a biased judge. The trial becomes the hot ticket for society folks. Rich folks come and entertain themselves. The judge sometimes had beautiful young society women sitting next to him. And he’s exchanging little flirty notes with them during the trial while these men are fighting for their lives. It was just obscene what happened. But ultimately, despite the heroic efforts of a very principled group of lawyers who defend these men, they are all convicted. Seven of them are sentenced to die. One was sentenced to hard labor.

Everybody thinks the whole thing’s over at that point. But they didn’t count on one person in particular, an extraordinary individual by the name of Lucy Parsons, who is married to Albert Parsons.

Now, if you don’t do anything else, read about Lucy Parsons because she’s an extraordinary figure. This is a woman of color who was married to a white man in Texas where it was illegal for Blacks and whites to be married at that point. She and Albert Parsons are probably the key leaders of the union movement, the revolutionary union movement, at that time. And this woman decides: Nobody is killing my husband and my comrades without a fight.

She goes on a speaking tour. She speaks to over 200,000 people in 16 states over that next year, sometimes bringing her two children with her. In that year, while all the appeals are being processed, there is a change in public sentiment. Originally, people were very hostile to the defendants.

One of the things to understand about this case is that these eight men accused of murder are accused on the legal theory that they advocated revolutionary violence (as a political abstraction) because they said that under certain circumstances working people have the right to use violence against their oppressors. Therefore, they were supposedly responsible for the bomb that was thrown at Haymarket.

But of those eight people, one of them was on a speaker’s platform, a wagon. The guy who was on the wagon was the one who said, “But officer, we are peaceable.” They’re accusing him of committing murder. He couldn’t possibly have committed the murder of throwing the bomb. Albert Parsons had left the rally before the bomb was thrown and was up the street having a drink at a bar. He couldn’t have committed the murder. He couldn’t have thrown the bomb. One defendant wasn’t even at the rally at all. And as this information came out, public opinion began to change, and there became more and more sentiment that the defendants should at least have reduced sentences, if not be exonerated completely. Unfortunately, there wasn’t enough of that sentiment. And in November 1887, four of the defendants are hanged. Two of them have their death sentences reduced to life in prison. And one is sentenced to 15 years at hard labor.

Years later, a progressive governor of the state of Illinois, John Peter Altgeld, reviews the entire case and pardons everyone. He pardons the living, the convicted leaders who are still in prison, and lets them out of prison. And those who were hanged, he posthumously exonerates all of them.

Almost three years after the executions, there is an International Labor Congress that is held in Paris on July 14, 1889. The key thing about that date is that it’s the 100th anniversary of the storming of the Bastille Prison during the French Revolution. A motion is made by a representative of the American Federation of Labor to make May 1st, May Day, International Labor Day. It passes. Ever since, virtually every other country on Earth celebrates May 1st as Labor Day. But not here in the United States because its origins are too radical.

During all the years of the Cold War, for instance, May Day was characterized as being a Russian, Soviet holiday and people here refused to celebrate it. There were no official celebrations in the United States. It was only with the resurgence of the working class movement in this country, in this century, that we’ve really seen May Day restored to its rights in the United States.

I had the privilege of working with one of the unions that fought to make sure that on May 1st, 2006, we had a gigantic demonstration in Grant Park, overwhelmingly of immigrant workers. If you ever want to have a good day, be on the stage at a rally in Grant Park and hear one of your co-workers read the words, “Today is a great day. The workers of Chicago have brought back May Day to the city in which it was born.” Those were the words that I had the privilege of writing for one of the leaders of the garment workers union. And as she read those words, I looked out and saw 750,000 workers [in Grant Park].

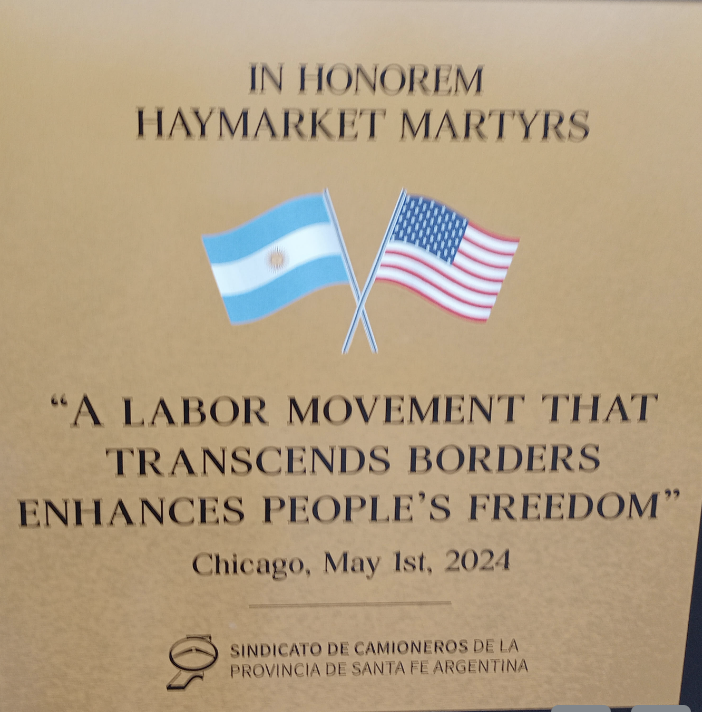

What does May Day mean today? A lot of people see different aspects of May Day. Some see it as being about the unions; “it’s about the fight for the eight-hour day.” Some people see only the ideological side. They see these guys were anarchists, and so they say, “I want to be an anarchist, I want to read about anarchism.” (In many ways, the Haymarket leaders were more syndicalists than anarchists.) But I think rather than looking at the Haymarket leaders’ specific views about ideological politics, to me, the thing that stands out most about May 1st, and the revolutionary leaders of that movement was their internationalism.

June 21st, 1886 is to me one of the days that should be remembered in history because that’s the day that Albert Parsons refused to scab on the immigrant workers. And he came back and he ultimately paid with his life. And the thing about May Day is that May Day is celebrated all over the world by people of all colors, of all genders, in all countries. It’s the one holiday like that.

And so what does that mean for us today? If you look at the poverty in this country today, if you look at the crisis in Gaza, what do students do? I can only tell you that the way I first learned about May Day was in May 1970. I was a teen-ager living in Washington D.C., active in the anti-war movement. I went to a demonstration in New Haven, Connecticut to demand the freedom of Bobby Seale and other Black Panther Party political prisoners who were on trial for their lives. Then at the end of that weekend, the United States announced it was invading Cambodia. And I was on the New Haven Green that Sunday when there was a motion that was put forward to have a nationwide student strike against the invasion of Cambodia. And it passed. And I distinctly remember raising my hand to vote in favor of that motion. A few days later, some of the students who carried out that motion at Kent State University were shot dead.

A few days ago, I received a communication from people at Kent State where they announced their support for the encampments around Gaza and their opposition to the National Guard being deployed on today’s college campuses. And you know that the Speaker of the House of Representatives in the United States has called for the National Guard to be used against these student protests today. Well, I’ve spoken at Kent State University twice, and I’ve seen what bringing the National Guard to a campus means.

So I think for all of us today, being a student is about questioning. It’s about learning. We all need to think very clearly about what we can do now to carry on this tradition of May Day. And with that, I would very much like to take questions or hear other people’s thoughts and their perspective.

Thank you very much.

Chris Mahin is a writer, speaker and teacher on contemporary U.S. politics and history, particularly on the significance of the American Revolutionary War and Civil war eras for today. He is the Electoral Desk on the People’s Tribune Editorial Board.