This story was originally reported by Amanda Becker of The 19th. Meet Amanda and read more of their reporting on gender, politics and policy.

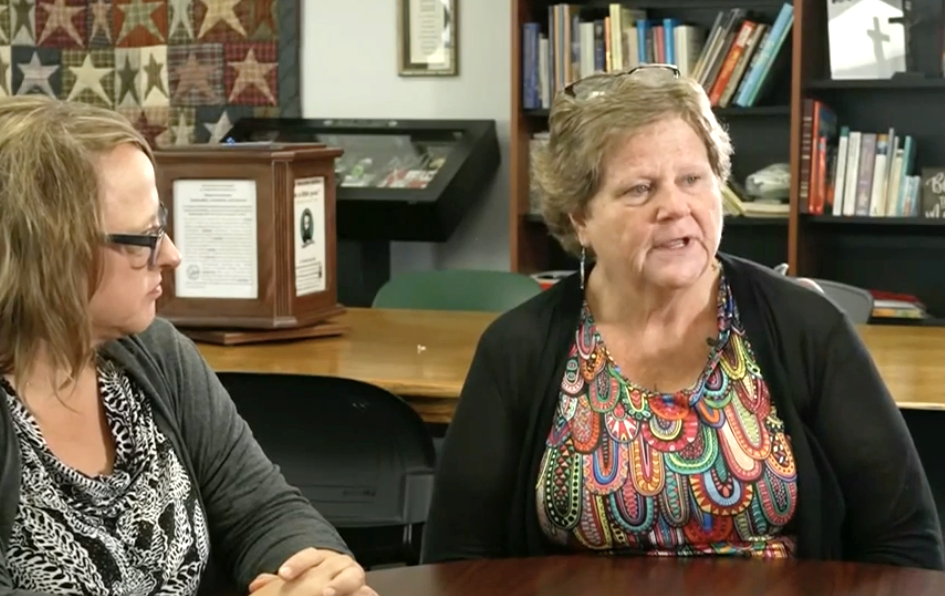

SPRINGFIELD, Ohio — Since last summer, Casey Rollins has braced for the day that children of Haitian immigrants would walk into the Catholic charity she runs without their parents.

That day has arrived.

First, one group of siblings. The next day, another. In one week earlier this month, nine children whose parents were no longer in the country came in with their extended families. Rollins and other advocates for immigrants fear these are the first cases in a looming avalanche of family separations that could overwhelm this city of about 60,000 in a central Ohio county that has in recent years absorbed an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 immigrants, many of them Haitians.

Rollins has worked closely with Haitian immigrants since becoming executive director of Springfield’s St. Vincent de Paul at the end of 2016. At first, the Catholic charity focused on providing language assistance to Haitian Creole speakers. Then she connected them to the charity’s thrift store for the warm clothing they would need to endure winter in Ohio and furniture and appliances to set up their new homes. The community center also offered computer access for them to apply for work permits and look for jobs in one of the companies that were drawn to the area by state economic incentives, like the massive Amazon warehouses and distribution centers in neighboring counties.

Employers specifically recruited Haitian workers via staffing agencies for hard-to-fill positions, their ads touting above-minimum-wage pay and benefits, luxuries for immigrants coming from a country ravaged by decades of political turmoil and a pair of earthquakes that killed and displaced hundreds of thousands of people. Arrivals in Springfield ticked up during the COVID-19 pandemic as more people emigrated from Haiti after the president was assassinated and violence worsened. Others came from big cities with deeply rooted Haitian communities, like Miami and New York, drawn by the promise of well-paying jobs in an affordable community that seemed to want them there.

(Maddie McGarvey for The 19th)

Then, during last year’s presidential election, Springfield’s Haitians became the target of a maelstrom of misinformation after someone posted online that they were eating their neighbors’ pets. President Donald Trump amplified the lie, as did Vice President JD Vance, who grew up an hour’s drive away, in Middletown, Ohio. Neither the city nor its newest arrivals could stop or control what came next. Neo-Nazi and white nationalist groups like Blood Tribe and Patriot Front disrupted community events and staged protests in front of City Hall and the mayor’s house. Phoned-in bomb threats forced the temporary closure of schools. In February, the city of Springfield and targeted individuals sued Blood Tribe over its intimidation campaign. Rollins, who lives across the street from the mayor, is one of the other plaintiffs.

It’s almost as if the threats and volatility only fueled and refocused Rollins, who does not accept a salary for her work. As the world around the Haitians in Springfield changed, the types of services offered by St. Vincent de Paul shifted, too — from helping them establish a life in the city to navigating the Trump administration’s immigration policies that threaten their ability to legally stay in the country.

On the day of his inauguration, Trump issued an executive order — “protecting the American people against invasion,” he called it — setting the tone for what was to come. He has since attempted to move up the expiration date of Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, which allows people from Haiti and other designated countries facing conflict or natural disaster to live and work in the United States for a set period of time. He also terminated a Biden-era program known as humanitarian parole, urging immigrants protected by it to self-deport and revoking their ability to work. (These and other pieces of his immigration measures have been challenged in court.)

There were 210,000 Haitians in the United States on humanitarian parole as of late last year. There are currently some 330,000 Haitians in the country with TPS, including thousands in the Springfield area. As things stand, the deadline for them to leave the country is February 3.

Over the summer, as immigration agents moved to detain and deport immigrants all across the United States, sometimes to countries that are not their own, Rollins and others at St. Vincent de Paul used every opportunity available to them to tell Haitian parents to get their U.S.-born children American passports.

(Maddie McGarvey for The 19th)

“If the child has a passport and the parents have to take the child with them, or have to give the child to a family in a different country — say they have to send them to a family member in Chile, or they have to take them to Chile — well, the child can’t travel to Chile without a passport,” she said.

The passports are also proof of U.S. citizenship, a critical shield at a time when even U.S. citizens are being caught in Trump’s immigration crackdown.

Rollins’ efforts soon bumped up against complications: a father has gone back to Haiti and is not present to sign the paperwork, a missing birth certificate must be ordered for a child born in another state. She also had to contend with the emotional ups-and-downs prompted by the helter-skelter nature of immigration policy implementation and shifting program end dates, she said.

The Haitians she works with, “keep thinking that there’s going to be a Hail Mary moment,” Rollins said. “They just have this unbelievable faith — I wish my faith was as strong as theirs is … But at the same time, I wish their faith was a little bit more pragmatic. Maybe they know better, and it is all going to work out. I hope to God they’re right. But I’m looking at this thinking, ‘No, let’s be ready. Let’s be ready for whatever comes.’”

Rollins is now preparing for a worst-case scenario that may be all but inevitable.

“I’m the town crier, literally and figuratively. That’s all I seem to do these days,” Rollins told The 19th during a recent interview. She was sitting at a table at St. Vincent de Paul, shading in this year’s Christmas card featuring her seven grandchildren — or, as she put it, the “seven little activists” who “go out on picket lines with me.” The cards often get political. Last year’s theme was “love thy neighbor” and featured Santa Claus looking out the window of the community center at a line of immigrants waiting to get in, drawn over a collage of headlines about Springfield’s Haitian residents. This year’s states: “I need to be able to tell my grandchildren that I did not stay silent.”

She dabbed at her eyes as she talked, wondering what might happen to the Haitian parents she has come to know and, most of all, wondering what might happen to their children.

On a recent Thursday, the local NAACP chapter convened a town hall at a Baptist church with the theme “preparation for mass deportations.” The seats were nearly full, and people stood in the back of the nave, lining the walls. Security was heavy; three police cars parked out front. NAACP President Denise Williams introduced a panel that included Rollins; Viles Dorsainvil, director of the Haitian Community Help and Support Center; Carl Ruby, a local pastor whose congregation is heavily invested in assisting local immigrants; and key city officials: Mayor Rob Rue, City Manager Bryan Heck, Police Chief Allison Elliott and Clark County Health Commissioner Chris Cook.

When it was her turn to speak, Rollins leaned into the microphone and introduced herself. “Hello. I’m Casey Rollins, and I’m a servant leader at St. Vincent de Paul. I am part of a ministry that is from all over the world.” She felt a pit in her stomach.

At St. Vincent de Paul, she noted, the “number one priority for us is always the children — always, always, always, think of our children.” Then, she laid out what has been obvious to her since the summer: The deportation of Haitian parents may very likely result in a “child custodial dependency crisis in this town, in this state, in this country.” Because parents may be deported after a raid, without the chance to decide whether to bring their children when they leave the country. And because they may choose to leave their children behind to give them a shot at living a safer, more stable life in the United States. For many of these kids, this is their country.

She explained that she and the workers at St. Vincent de Paul had already helped Haitian immigrants obtain passports for their U.S.-born children, sometimes at a rate of three to four a day. But, she said, the passports wouldn’t be enough.

A ripple went through the crowd when Rollins told them about the nine children who had come to St. Vincent de Paul after their parents’ deportations. There were audible gasps. When it came time for questions, nearly every one of them was about the children.

Cook added that there are more than 1,300 children in Clark County who have been born to Haitian parents in the last few years alone, meaning all of them would be citizens. The number is likely far higher, plus thousands of children who emigrated from Haiti and more who were born in another country during their parents’ immigration journey.

“The volume of need for this service far exceeds the service we’re able to provide,” Rollins cautioned. “Please, please, bear with us all as we cry a lot, as we rage a lot. Feel free to do that with us. Come see us if you’d like to be a part of this initiative and this effort.”

(Maddie McGarvey for The 19th)

From a legal standpoint, assisting minors remaining in the country without parents may require action in two different court systems: family and immigration. Children who are U.S. citizens will need legal guardians to sign paperwork for passports and other documents and to handle routine matters like school enrollment and doctors’ visits. Many will need to pursue a type of guardianship that is triggered by an emergency event, like a deportation or detainment, in order to maintain custody of their children while they are still here.

Noncitizen children will also need guardians — and they will have their own immigration cases to contend with.

Rollins and others assisting Haitian families want to find a way to avoid a potentially chaotic period when decisions cannot be made on a child’s behalf because they don’t yet have a legal guardian. To succeed, they need to find lawyers to take cases that touch both court systems.

Rollins — a 66-year-old from a large Irish Catholic family who taught school for 34 years and educated many of Springfield’s leaders — is a woman of faith who also believes in the power of community. That’s what she’s leaning on these days.

About two weeks ago, a juvenile court magistrate texted her a photo of the business card for Bridget Emiko Jackson, a family court lawyer who was just telling the magistrate that she wanted to take on more immigration cases. Within minutes of receiving the text, Rollins and Jackson were talking on the phone.

“I couldn’t get out of the courthouse parking lot before I heard from Casey,” Jackson said. “Next thing I know, I’m working on a presentation.”

Jackson is putting the finishing touches on a series of slides that lay out what a legal process could look like to assist children with guardianship. A friend and former law school classmate she now practices alongside has jumped in to assist. Their goal is to have it ready for potential funders, volunteers, other lawyers, community groups and relevant government agencies as early as this week.

(Maddie McGarvey for The 19th)

Rollins knows there will need to be many more people like Jackson to handle the number of guardianship cases that will very likely arise under the current climate — and if the February deadline for the end of TPS holds. She keeps hundreds of informational sheets about filling out child passport applications and creating family immigration raid emergency plans on the long table just past St. Vincent de Paul’s front doors. Two volunteers spent last week fully focused on immigration matters as others began to pack 1,200 Christmas food baskets. Some will be hand-delivered to Haitian families.

She noted that already, people have reached out to help, at times “transcending their politics.” Groups like Springfield Neighbors United, a critical partner in the passport effort, and G92 have formed to help the cause. Leaders from the Nation of Islam are working in concert with Catholic nuns. Rollins hasn’t always agreed with the city’s elected leaders, but works with them closely because, she said, “I believe in people who believe in people.”

And she is choosing to believe in the underlying goodness of the people of Springfield, where she grew up, married, worked and raised her son. She is choosing to believe they will not let their Haitian neighbors down.

I’m Amanda Becker, The 19th’s Washington correspondent. I like to use my perch to examine the gendered aspects of power and how gender shapes policy. Since policy isn’t made in a vacuum, my favorite type of political stories draw across institutions and movements to examine what I call the “connective tissues” of our democracy.

I’ve been on the beat for nearly two decades, covering the White House, the Supreme Court, Congress, multiple presidential elections, and scores of House and Senate campaigns. Before joining The 19th in April 2020, I spent nearly eight years at Reuters, where I was embedded with Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, and several before that at CQ Roll Call, where I covered lobbying and influence.

I was a 2023 fellow at the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University. My first book, “You Must Stand Up: The Fight for Abortion Rights in Post-Dobbs America,” was published by Bloomsbury in September 2024. My byline has appeared in The Washington Post, The New York Times and USA Today, among other publications.

I grew up in Ohio and perpetually long for Cincinnati-style chili. I received a bachelor’s degree in political science with honors from Indiana University and a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Southern California.

My work is free to consume and free to republish because of contributions from readers like you. A donation of $19 goes a long way toward sustaining our nonprofit newsroom.