CANNONBALL, ND — The Standing Rock Sioux tribe of North Dakota got word of the Dakota Access Pipeline and its revised route in early April. Originally, the pipeline was to snake through Bismarck, but that was deemed too dangerous for the highly populated area if it were to burst. The solution: run the pipeline through reservation lands, fewer people would be at risk.

The Dakota Access Pipeline would be transporting sweet-light crude oil through 50 counties in four states—North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa and Illinois—while crossing the Missouri River not once, but twice.

Pipelines are notorious for breaking, so it’s never a matter of “if, but” when.” And when it does burst it would take just five minutes to contaminate the water. A short two hours later, the polluted water would reach the Cheyenne River, a tributary of the Missouri River, which the reservation has relied on for generations. The contamination would leave absolutely “no warning for us,” said Cheyenne River resident Jassilyn Charger. “Some of us will be drinking it without knowing.” Both tribes have no filters on their intake system. Their drinking water would be directly mixed with crude oil—among the worst kind of oil that can be introduced to the environment because of the heavy saturation.

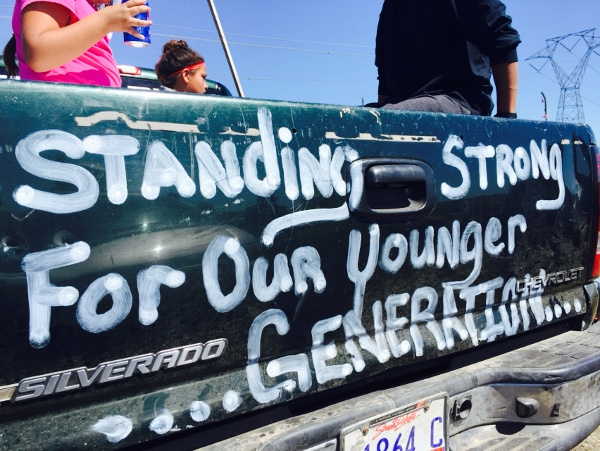

Since April, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe has been tirelessly working to protect the sacred waters. “Mni Wiconi” in Dakota/Lakota/Nakota means “water is life.” It is this mantra that is echoing throughout the world now in the “No DAPL” movement to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Four months into the movement, the protection of the water continues to strengthen as Cannonball, N.D., becomes the forefront of those who stand in solidarity with the Standing Rock Sioux, Oceti Sakowin collective Dakota, Lakota, and Oglala nations. In just one week, the front line protector numbers grew from a handful to as many as 1,500 people strong. The Standing Rock Sioux officially put the call out for help, and in a matter of days, people from tribes across the county and those of “The Medicine Tribe,” comprising of individuals of all backgrounds, made their way to stand together to protect the sacred water.

The two camps—another had to be added to accommodate the mass influx of water protectors—are a mix of races and represent a powerful statement to the world. It’s a display of unity among native people, or people of color and those of European ancestry. Native American tribes, who once stood against each other, are now coming together, after years.

The statement is simple: We are all one race—the human race, and we all need water to survive; we all need land to thrive—and now, for the generations who follow. The peaceful protection is what makes this a sustainable stance.

For now, no drilling can happen, thanks to the peaceful work of the front line protectors and to the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s lawsuit against the Army Corps of Engineers who approved the route change in early April. The hearing was held Aug. 24 with a decision to be made by Sept. 9. If an appeal is necessary, a final verdict will be made by Sept. 14th.