Editor’s note: The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of women winning the right to vote in the United States. To commemorate that important victory, the People’s Tribune will be printing articles this year about different aspects of the fight of women workers for equality. This first article describes the historic “bread and roses” strike by Massachusetts textile workers in 1912.

“We want bread—and roses!”

“Bayonets cannot weave cloth!”

“Better to starve fighting than to starve working!”

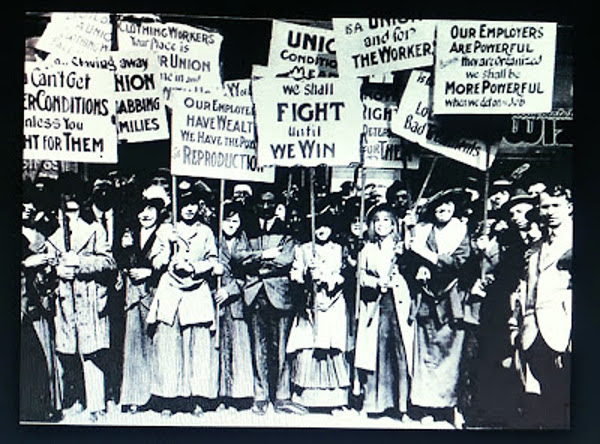

More than a century ago, thousands of men, women, and children shouted those slogans—in many different languages—in the bitter cold of a Massachusetts winter.

On January 12, 1912, thousands of workers walked out of the textile mills of Lawrence, Massachusetts. Almost half were women. Many were immigrants.

Lawrence, Massachusetts was a city of 86,000 people in 1912, and a great textile center. Within a one-mile radius of the mill district, there lived 25 different nationalities, speaking 50 languages. By 1912, Italians, Poles, Russians, Syrians, and Lithuanians had replaced native-born Americans and western Europeans as the predominant groups in the mills.

The cost of living was higher in Lawrence than in the rest of New England, and the wages of the textile workers were totally inadequate. The city was one of the most congested in the United States, with many workers crowded into foul tenements.

The immediate cause of the strike was a cut in pay. Lawrence was quickly transformed into an armed camp, with the police and militia guarding the mills.

The Lawrence strikers created a democratic form of organization in which every nationality of worker was represented. The strikers voted to demand a 15 percent increase in wages, a 54-hour week, double time for overtime, and the abolition of the premium and bonus systems.

The agents of the mill owners struck back. When the police and militia tried to halt a parade, a bystander, Annie LoPezzo, was shot dead. That same day, an 18-year-old Syrian striker, John Ramy, was killed by a bayonet thrust into his back.

Concerned that the growing outrage over the conditions in Lawrence might lead to public support for lowering the woolen tariff, the mill owners began to look for a way to end the strike. First the largest employer, the American Woolen Company, came to an agreement. Then the others followed. The workers won most of their demands. By March 24, the strike was officially over. It was a tremendous victory.

The victory at Lawrence showed that women workers and immigrant workers would not only support strikes—if given the chance, they would gladly lead them, and lead them well. The strikers in Lawrence won their demands because they never let themselves be divided on ethnic or gender lines, because they were militant (and creative) in their tactics, and because they found a way to appeal to the conscience of the public.

The Battle of Lawrence is summed up in the strike’s best-known slogan: “We want bread—and roses!” The Lawrence strikers wanted more than a wage increase. They were inspired by a vision of a new society, one where the workers themselves ruled. In this society, every human being would have “bread”—a decent standard of living. They would also have “roses”—the chance to learn, to have access to art, music, and culture; a society which would allow the flowering of everyone’s talents, the full development of every human being.

On this anniversary of women winning the right to vote in the United States, we should learn from all those who made that victory possible—including all the brave women industrial workers who waged their struggles before women had the right to vote in the United States.

If we all act with as much foresight and courage as they did, we can create a world with both bread and roses for everyone.