In August we saw 4.3 million U.S. workers, almost 3 percent of the entire American workforce, quit their jobs, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Since the beginning of 2021, 7 million workers have left their jobs.

This past October has been marked by a wave of strikes (or near strikes) involving thousands of workers across the country, including John Deere, Nabisco, Kellogg, as well as distillery workers in Kentucky and 60,000 members of IATSE. This trend began years before the pandemic.

Economists, labor leaders and pundits are scrambling to explain “the new phenomena” to lead this movement. Everyone wants to attribute this “new” movement to their organizational efforts. Clearly, there are as many reasons as there are individuals who are leaving their jobs or participating in collective activity, whether organized by existing organizations or not.

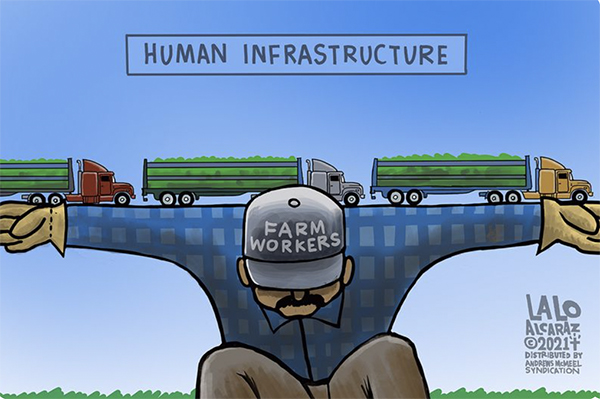

The pandemic intensified the personal and objective conditions that workers live and work in under capitalism. A growing resistance to these conditions has increased over the last few decades. Workers (especially “essential” workers,) have become keenly aware of their conditions of work and their value from the point of view of the corporations and the system. They have become profoundly aware of the value of the lives of their grandparents, parents and families in their communities to themselves, recognizing that no one will care for them and their children but themselves. Workers lost hundreds of thousands of relatives and friends to a system unprepared to protect them. This can accelerate the growing consciousness of our class identity.

We have seen a growth in the broad social movement for change, especially after the George Floyd murder against police brutality and racism. A part of that movement overlaps with low wages, rent increases and bad working conditions—which is driving workers to assert their interests, despite the drive to use the race issue to divide workers.

The battle to articulate the demands of these movements and shape the vision and program of the broader movement of the working class is continuing to increase in intensity.

* * *

Voices of workers: Why they’re striking, organizing walkouts and unions

Editor’s Note: Below are excerpts from workers about why they are striking, organizing walkouts or unions. Material is from various news media and social media.

Video Still / NBC News

30,000 Kaiser Permanente employees threaten to strike

“Denise Duncan, president of the California union and a registered nurse, told The Washington Post: “There’s increased pressure placed on nurses for what we call the churn. Get the patient in and get the patient out,” Duncan said. We need more hands on deck . . .”

“A two-tier system is pretty draconian in and of itself. Because it starts off paying workers so substantially less than current employees, it creates division. So if you have an employee who is one or two years in and the two tiers kicks in, that new employee two years later is making 26% to 39% less than that other employee. And at one point, that workforce will be divided between the first tier and the second tier. So what it creates then is basically a second-class set of workers…” (Washington Post)

10,000 John Deere workers reject contract and strike. . .

Workers say the pandemic gave them a new sense of worth. The strike affects 14 plants in Iowa, Illinois, Kansas, Colorado and Georgia.

“The company is reaping such rewards, but we’re fighting over crumbs here ….”

“I was happy to see we didn’t come back with a tentative agreement . . . “It restored some of my faith in my international.” (Washington Post)

Starbucks workers vote for a union

“With the pandemic and labor shortages — the fact that for once we’re not totally disposable, they need us — it was the perfect time . . .”

“I’ve had drinks that take two blenders to make — a Frappuccino with foam [said] a shift supervisor in the Buffalo area. “I want to do that. But then I hear about how drive-through times are not fast enough. It’s hard to know what they want from us.” (New York Times)

Frito-Lay workers:

‘We want to see our families . . .” “I’m done with giving everything to Frito-lay’I’m really amazed at the community support . . . It makes you proud to be a part of this community.”

“It’s scary but it’s exciting . . . I have so much hope for this strike that we will finally get what we’ve needed—the guarantee of getting to see our families, and earning a living wage to support those families.”

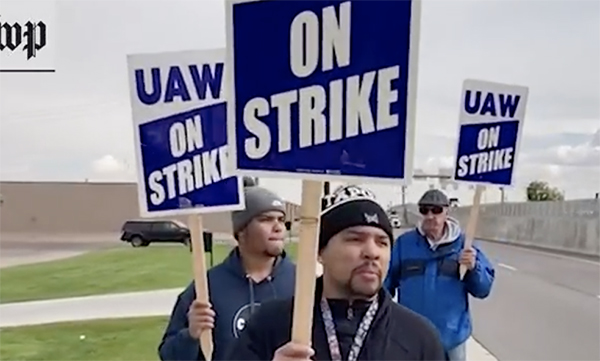

UAW workers, Iowa:

“When you factor in the pandemic, being deemed essential workers, and in our case, having a company turning a record profit, the CEO giving himself a 160 percent raise, and giving a 17 percent dividend raise, we kinda feel like we’re left to kick rocks,” said a UAW member at Iowa’s Davenport Works who asked for anonymity for fear of retaliation.

“The quicker we can put a financial dent on them, the better off we are when it comes to showing them that we mean business,” said a Davenport worker. (Washington Post)

McDonald’s workers walk out in Bradford, PA

Dustin Snyder, 21, and now former Assistant Manager at McDonald’s asks: “Why would you want to work for a company that doesn’t value you?”. . . You’ve been here for five years . . . What have you got for it? Nothing.”

“Shakira Griffin, 17 year-old homeless McDonald’s worker said, “[In the walkout] I was doing stuff with people besides arguing . . . I was standing up for myself and what I deserve. . . I’ve never done that before.”

“Dustin Snyder: “[I] considered going to college to become a pastor … I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life, and it felt meaningful …” [Snyder said he did not have the money for school and fell out with his church.] “…I did not regret the walkout. [I] “refused to bow down to the big scary corporation.”

(The above are excerpts from a story about a McDonald’s walkout by Greg Jaffe, The Washington Post)