The People’s Tribune’s Sandy Reid talked recently with Ken Brown, second-year math PhD student at UC Davis and UAW union member, about the significance of the now over one-month long University of California student worker strike, the demands, particularly of the lowest paid workers, the power of the UC system and current status of the settlement process now underway. We welcome the thoughts and perspectives of more student workers too. Send to peoplestribune@gmail.com

People’s Tribune: Please tell us how you became involved in the UC student strike.

Ken Brown: I was enthusiastic to join the union when I came to Davis last year. I was proud to be a member and encouraged other grad students to join, but I got much more involved when we had the strike authorization vote early in the fall quarter [October 2022]. I started knocking on doors and calling people and working with other people in the math department to get our colleagues to vote on strike authorization. And since the strike began we’ve been more involved; we go to the picket line, follow the contract negotiations, see what people want, and try to communicate up and down the chain.

On the 15th of December, our bargaining team agreed to a tentative agreement after mediation. The bargaining team was split, but the majority voted to accept this agreement, and now it’s been sent out for ratification by the whole union body. The voting opened Monday morning, [December 19] and it’s going to end on Friday [December 23]. If the members vote to accept it, that’s the new contract and the strike’s over and we move on. If we don’t vote to accept it, then the strike continues, the bargaining continues, and we’ll see what more we can get.

PT: Do you have any sense of what’s going to happen? We’re hearing there’s dissension.

KB: Yes, there’s a lot of dissension. I don’t know how it compares to the average union contract negotiation. There’s a more concessionary faction on the bargaining team and a part of the bargaining team that wants more and believes that a longer strike could get us more. The truth is I don’t know how the great bulk of the rank-and-file members feel about the tentative agreement; there’s some gains in the contract, but there’s a lot we were hoping for that the contract doesn’t have and a lot of people will still be rent burdened. One issue for me is the lack of movement on childcare subsidies and dependent healthcare. If you have kids, then either you have rich parents or you go into debt or you can’t go to grad school. That doesn’t seem right to me.

PT: Could you address the sentiment stated by some that ‘student workers make so much money already there’s no need to strike’ (which seems to diminish that California is one of the highest rent states in the nation).

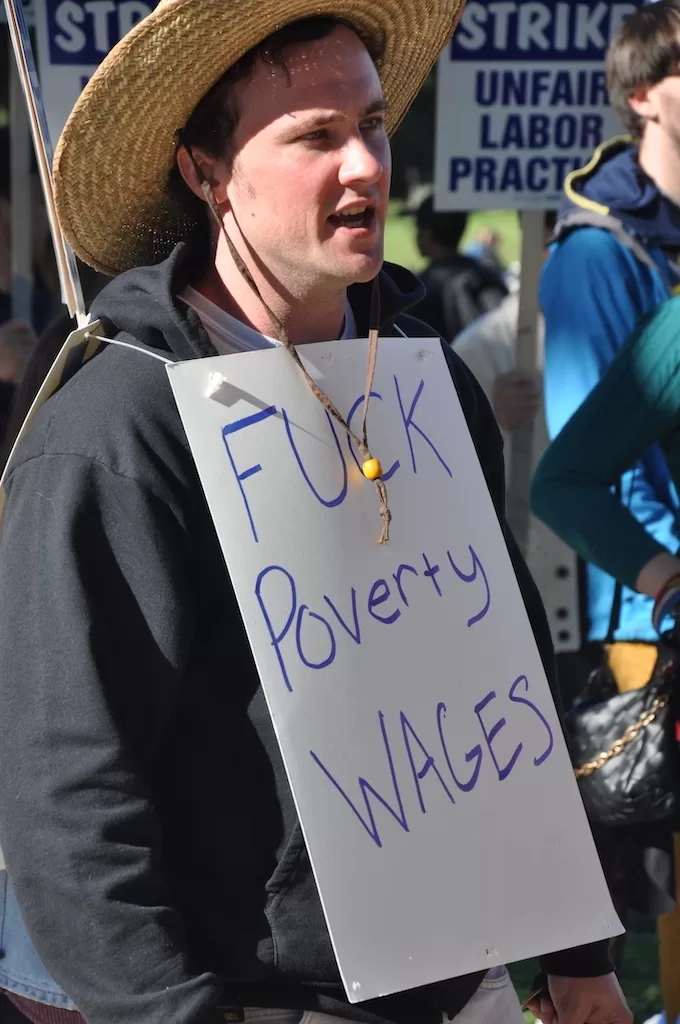

KB: We’ve been using rent burden as a proxy for how pay compares to the cost of living. Like how many people are paying more than 30% of their monthly income on rent? Depending on the campus, that can be 40%, 50%, 60% percent of workers are rent-burdened, even with the raises in the tentative agreement. If we were in Tulsa or Phoenix or somewhere, then maybe this would be a livable wage. But in California, where the rent is so high, our pay doesn’t go nearly as far.

Childcare is another really serious problem. I don’t have kids, but I was speaking to a friend in the math department who does. She said that if your kid is not in school yet, you can pay close to two grand a month. Our monthly pay in the old contract is like $2,700 a month. So, you know, do the math and see if you can figure that out. We do have subsidies but they’re inadequate: for a child under 12, the subsidy is like $1,300 per quarter, call it $450 a month. Maybe that’ll cover a quarter of your childcare costs if you have one child.

PT: I saw a student striker tweet say, “This [strike] is going after the totality of the UC system.” Are underlying changes taking place in the university system, perhaps a result of today’s changing economy? Some say the UC system here and colleges elsewhere in the country are driven more by the profit motive, corporate ties and corporate influence.

KB: My father grew up in California and he went to UC Berkeley, which was, then, as now, a prestigious public university. And he paid, I think, $700 in fees per year. Now I think the undergrads’ annual tuition is $15,000 or so? I don’t know exactly but it’s a hell of a lot more money. There’s been a long slow process of moving the cost away from taxpayers and to students’ tuition, and there’s also a whole college debt story. But there’s been less state support for higher education across the country, including in California where it’s very prestigious but very expensive. There are big endowments, but maybe they’re getting away from the sort of public service function. I think when you have the organization becoming semi-private, it means they care a lot about tuition dollars, the endowment, about alumni relations and donations; I do think the UC is becoming more like a Harvard or a Stanford. As a state institution it is meant to give kids from California a good education at a low price. But sometimes it feels like: ‘come here, pay a ton, and then go work for McKinsey or Goldman Sachs and don’t forget to write us a check.’

PT: And today, with technology replacing so much labor and also now with the layoffs resulting partially from that, the world has changed so much. Just wondering if the university really needs to train as many workers as before?

KB: I think that’s a reasonable question to ask. I think sometimes about the product that’s being offered and about administrative bloat and there being too much of this and that. But the core costs of learning at the university like academic labor costs haven’t gone up nearly as fast as tuition has gone up. The number of incoming undergraduate students peaked in 2010, but it’s pretty similar to what it was in 2010 now, and it’s not going to fall off a cliff. And we’re always going to need public institutions to provide efficient, low-cost, high-quality education to people who are going to be doctors and software engineers and all that. So, yes, the UC is a vital institution. It has served me well. It has served many other people well. But I do think that the whole institution of American higher education is moving in a direction that’s not great.

PT: And, in relationship to the strike, it seems the American people may have lost an understanding of the importance of U.S. labor history.

KB: I was very gratified to get pulled into that long arc of labor history. Our union forebears fought for these good things we have. My brother was involved in the UAW in a different occupation and I was happy to get involved. This is a long fight and it’s been fought in a lot of places by a lot of people a lot of times, but it works.

I would like to add that this has been the biggest academic workers strike certainly in the US and I’m assuming anywhere ever. And I encourage other people, not only academic workers elsewhere, but also people in all kinds of industries.

We fought and we made real gains. Maybe not as much as we wanted, but this contract is a lot better than what we were offered before the strike. And we got that because workers got together and started a union and we joined the union and we went on strike. When we come together we have more power and we get better contracts. I would encourage other people to think, ‘hey maybe if we came together and started a union then we could get better pay and a better contract.’